I had begun to read the Bible in a year about two years ago; it seemed something of a fashion during the long months of the lockdown. And I simultaneously scribbled some little notes. I shall use those to populate this blog until I can get some new content in. That will happen when I have completed the relocation to Louth. But here’re my ramblings about the Gospel of S. Matthew.

It’s still safe to consider S. Matthew’s Gospel as being written the first, which is the traditional story, although a large portion of modern scholarship has succumbed to the idea that Saint Mark’s Gospel is prior, because of its smaller size. The idea seems to be that the shortest comes first, like a skeleton, which is later fleshed out into newer versions. There’s also this reasonable if entirely un-evidenced idea that there was a common body of ‘Jesus sayings’ that the scholars call Q, from which the evangelists (except Saint John) drew upon to construct their several essays. It’s all way up there: clever ideas thought up by clever people, you see. I’ve always thought, in my own reading, that these modern scholars picture the Apostles and Evangelists as scholars sitting in writing rooms to write, with bookshelves of reference books behind them. When you consider that many of these same scholars think that the Gospels were all written decades after the Ascension of Christ, and not by the Apostles and their disciples but later Christians, you can see why this whole idea of assembling by reference to other traditions fits in. I may refer to this theory as the priority of Saint Mark’s Gospel…

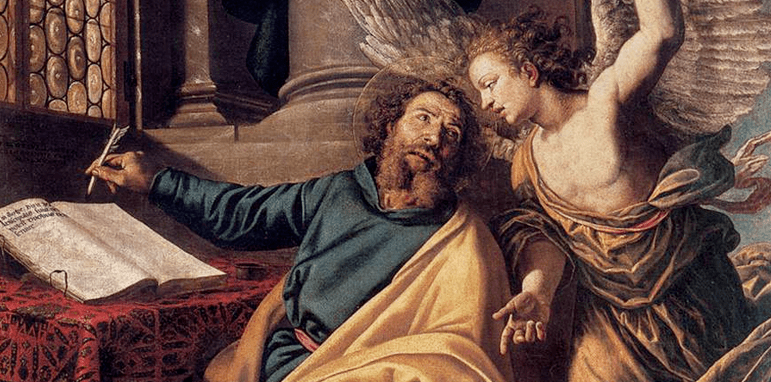

But, the older idea, as I said, may still be held. The Apostles had a mission and needed to leave the Holy Land at some point, possibly at some time in the late 50s. They required a working text of the Gospel to carry on to the countries they would visit. They must have generally used Matthew’s Gospel, the only one written at the time. He was one of the Apostles, of course. I know that at least the Apostle Bartholomew’s copy was left behind in India and found later (according to Eusebius’ history); and, of course, the Apostle Barnabas was buried with his copy. The mission of the Apostles, as also of Christ, was to the Jewish people, and the Gospel of Saint Matthew is full of references to the Hebrew Bible, what we call the Old Testament. Mark’s Gospel, written later, when the Apostle Saint Peter had arrived in Rome and Mark had joined Peter’s disciples there, is shorter and has some particular reference to Saint Peter, as it naturally would. It’s similarity to Saint Matthew’s Gospel may simply be explained by the fact that that was available in Rome and regularly heard, alongside the Holy Father Saint Peter’s own reminiscences. Saint Luke’s Gospel contains new information, such as in the infancy stories, and must have required further input from local Christians in the Holy Land (such as the Blessed Virgin) and is certainly from later on. Saint John’s Gospel is generally considered to be the last of the four, although it contains some very early, first-hand-witness information.

Flipping through Matthew’s Gospel right now, it’s surprising how short it feels, how abbreviated. The Gospels were not meant to be biographies of Christ, although they provide biographical information. They were concerned rather with presenting Christ as the fulfilment of the Promise. Matthew therefore provides an adjusted genealogy at the very beginning, to demonstrate that Christ’s arrival was carefully planned. Saint John the Baptist is introduced and surpassed. The Apostles are appointed, the inner circle first – Peter (along with his brother Andrew), James and John – and then the rest. There is the great Sermon on the Mount, between chapters five and seven, a first catechism, we might say. Then come the long stream of miraculous works, interspersed with confused Jewish leaders – pharisees, mostly, but increasing numbers of scribes and Sadducees (Jerusalem priests and their associates) – asking why such an orthodox Jew doesn’t observe all the various purity laws of the people. The disciples are then sent on the mission. John the Baptist is soon killed by Herod, the ethnarch of Galilee, and Christ takes Himself away from Galilee. In the midst of new attention from the Pharisees and the Sadducees, Christ prepares for His sacrifice with the Transfiguration on the mountain and the procession to Jerusalem. The controversies with the Jerusalem authorities climax with the terrible parables of the vineyard owner whose servants and son are killed by the vineyard keepers and of the king whose son’s wedding feast is not attended by those invited. The implied abandonment of Jerusalem by God brings a new fury into the hearts of the Jerusalem authorities, who arrange for Christ’s arrest. He establishes the new covenant, is tried, tortured, killed and returns from the dead. The Church then receives the command to go forth on the mission.

It’s the greatest story ever told, a romance and a love story. Read the whole thing here.